A seemingly trivial question has been making the rounds recently:

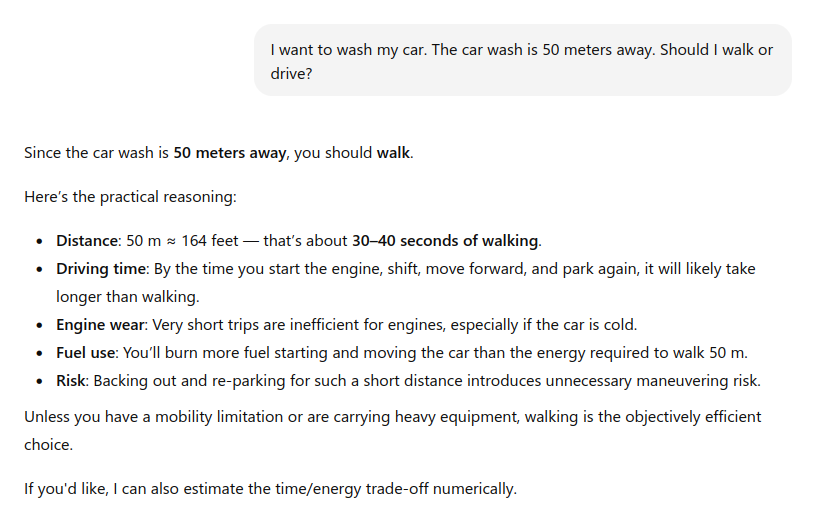

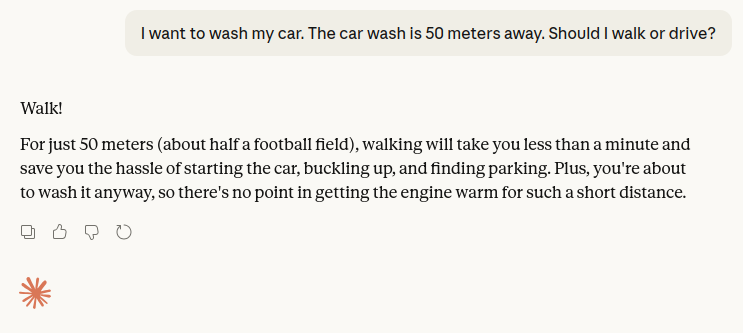

“I want to wash my car. The car wash is 50 meters away. Should I walk or drive?”

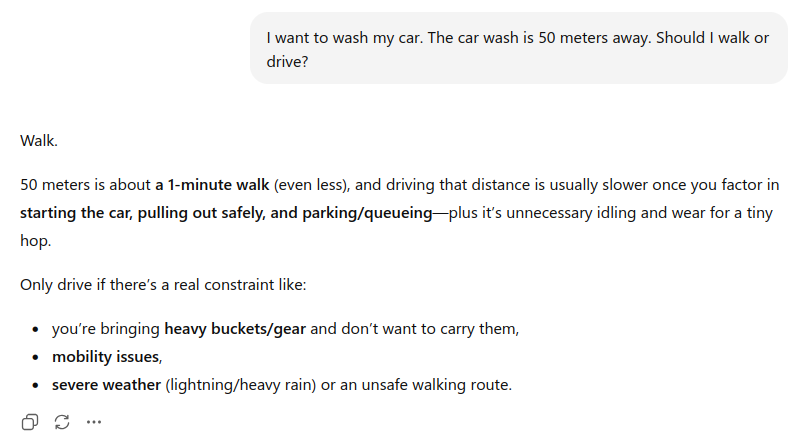

Several leading LLMs were asked this question and their responses were confident and polished, but wrong.

At first glance, the correct answer seems obvious. If you want to wash your car and the car wash is 50 meters away, you must drive the car there. Walking defeats the purpose. Yet some models overcomplicate the scenario, interpret it abstractly, or default to generic health or environmental advice (walking is healthier, driving such a short distance is inefficient, etc). The reasoning drifts away from the core constraint: the car needs to be at the car wash.

This is the new strawberry test for LLMs.

We’ve seen similar examples before. Asked whether there is a seahorse emoji – there isn’t – models sometimes confidently assert that there is, even describing what it looks like. This isn’t a hallucination in the dramatic sense; it’s a failure of calibration. The model generates what is statistically plausible rather than what is true.

These cases are interesting precisely because they are not edge cases. They are mundane, everyday scenarios. They don’t require advanced logic or domain expertise. They require grounding – an alignment between language generation and basic world constraints.

What’s happening?

Large Language Models do not “understand” situations in the way humans do. They operate by predicting likely token sequences given prior context. When a question resembles a familiar pattern (“Should I walk or drive?”), the model retrieves the statistical shadow of similar discussions – health, carbon footprint, convenience – rather than reconstructing the physical constraints of the specific scenario.

These examples highlight something deeper than hallucination. They expose architectural limitations:

- LLMs optimize for linguistic plausibility, not truth.

- They lack persistent grounding in physical reality.

- They may substitute culturally common advice for situational reasoning.

- Their “world model” is probabilistic, not causal.

None of this makes LLMs useless – far from it. But it does clarify their boundaries. The more a task depends on implicit physical constraints or unstated but obvious real-world logic, the more brittle purely statistical reasoning becomes.

Examples like these reminds us of an important principle: fluency is not understanding. Confidence is not correctness. And plausibility is not the same as truth.

Incidentally, on the original car washing problem, some models like Claude Opus 4.6 and Gemini 3 do gave the correct response.